Article 42 of the Lisbon Treaty provides that the common security and defence party “shall be an integral part of the common foreign and security policy”. The article also states that this would entail the “progressive framing” of a “common Union defence policy” which would lead to a common defence policy “when the European Council acting unanimously so decides”.

However, when the Irish people rejected the Lisbon Treaty in 2008, the Member States of the EU agreed that it was Ireland’s choice alone as to whether Ireland would choose to be part of a common EU defence, and Ireland, in order to secure the support of the people in a second referendum, inserted an express prohibition in Article 29 of the Irish constitution on on Ireland agreeing to any unanimous decision to establish a common defence if it included Ireland.

In short, although the EU Member States gave us an opt-out of common defence, we actually altered our constitution to prohibit Ireland from becoming part of an EU common defence that includes Ireland. Only a referendum in Ireland can change that.

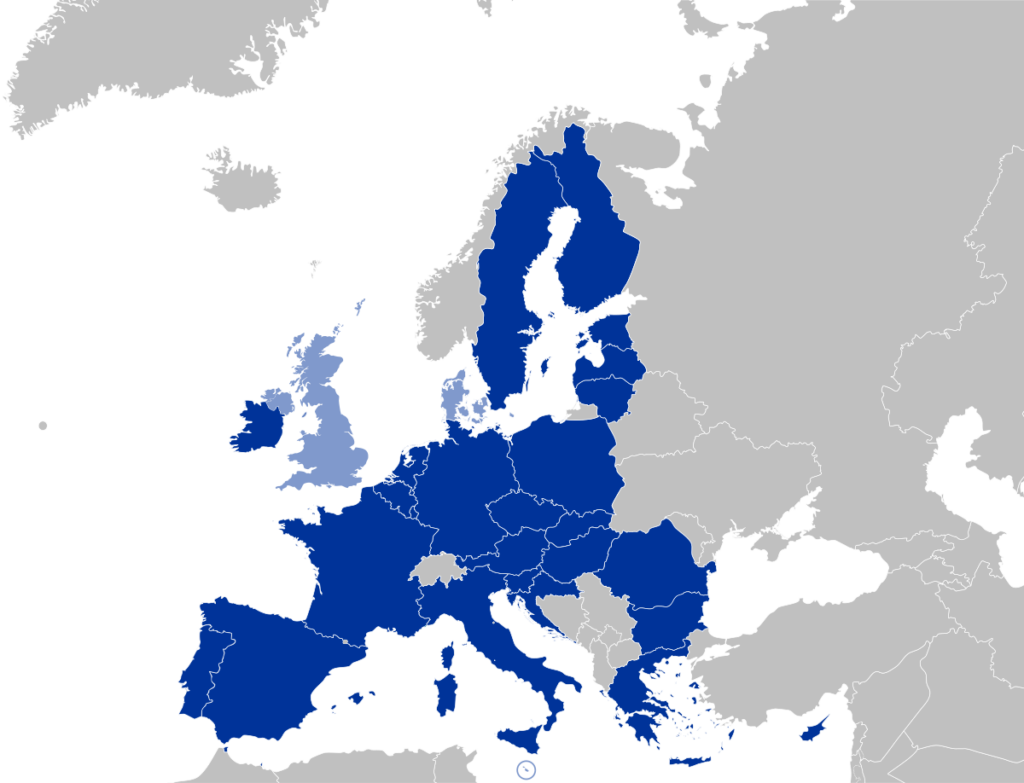

Ireland is not alone in having an opt-out from an EU common defence; several other traditionally neutral member states also enjoy that status.

Does this matter much? It does, in that Ireland , as far as EU common defence is concerned is, in constitutional terms, semi-detached from those member states who can form a common defence and an EU army. Ireland’s defence forces cannot form part of an EU army and the sole right of the Oireachtas to establish and maintain any military force in Ireland precludes the establishment of EU military bases on our territory.

Various EU politicians are now suggesting that the creation of an EU Defence Union is the next great integrationist project, and that such a defence union is essential for the further political integration of the EU.

Ireland will, accordingly, be able to participate in a very limited way in any EU defence coordination measures. That explains the very limited steps that the Dáil agreed in relation to PESCO last week.

Defence is just one area where Ireland has to be very careful in adopting stances at the EU Council these days.

Ireland unambiguously wants and needs a soft Brexit package to emerge over the next 24 to 36 months. We need the UK to be given a very close tariff-free trading partnership with the EU – one that is as close as possible in effect (if not in form) with the Customs Union. Such an outcome guarantees an invisible, frictionless border on this island.

We also need a regime that under-pins tariff-free trade in goods with a very clear prohibition on state aids which would distort cross border trade in goods. That is what regulatory alignment means in that context.

But our needs in that regard are shared by the rest of the EU; there cannot be tariff-free trade in goods at Calais if the UK is entitled to engage in state aids that amount to subsidisation of those goods.

As regards unfettered access to the Single Market in services, including financial services, the UK is going to have to accept that that the EU simply cannot allow the UK to enjoy such access combined with free trade in goods; any concession that the UK can have all the gain but none of the pain of EU membership would almost inevitably lead to the break-up of the EU.

Is Ireland concerned by the exclusion of the UK from the single market for services? Probably not.

Another aspect of Brexit that our government must bear in mind is the unique set of relationships that exists between the two parts of Ireland and between those two parts of Ireland and the island of Britain. Brexit cannot mean that those relationships are cast aside – now or in the future. Our strategy for Europe’s future must bear that reality in mind.

We cannot aspire to Irish unity if we meekly witness and support each part of the island being towed apart by the heavy tugs of an isolationist Britain and an integrationist EU. The new reality that we now face requires us to pursue a very nuanced foreign policy with all our neighbours – we cannot be the “me too”, unquestioning enthusiasts for the implementation of radically diverging policies and strategies on either side of the English Channel either.

We have got to focus on the aspirations of those countries in the EU who do not wish to be subsumed into a strong Franco-German hegemony. Some of them, such as the Baltic states, have very different security concerns from ours; but many have a strong fear of being sucked like weak satellites into an integrationist orbit in which France and Germany call all the shots. France wants to militarise Europe. But who does Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania trust to protect them –a Franco- German euro-army or Nato?

Angela Merkel’s disastrous demand that all of the central European states open their borders to the migrant wave that she encouraged impressed on many of those states just how oppressive further political integration might become.

I was struck be the article written by veteran FT Irish correspondent, Vincent Boland, in the Irish Times last week in which he seemed to be calling on Ireland to soften its positions on Irish red-line issues in a gesture of gratitude and/or support for Angela Merkel in what appears to be a moment of crisis in her political career following the collapse of the German “Jamaica Coalition” talks. I wasn’t clear just what concessions were being urged on us by Vincent Boland , and he did not specify them either.

The crucial thing for us to remember is that Martin Schulz, the SPD alternative potential coalition partner for Merkel, is no friend of Ireland’s on any of our red-line issues for all the reasons that I mentioned here last week.

And my old pal, Guy Verhofstadt, seemed to be revelling in Theresa May’s difficulties last week as well. He does not favour, deep down, the closest tariff-free, free-trading partnership with the UK that we aspire too. He has a punitive attitude to the UK and Brexit which comes to the surface from time to time.

What are we to make of the UK ministers’ double-speak and back-sliding in the last week? Simply this – Brexit was sold on a lie to a UK electorate sick to its teeth of austerity. That lie is now becoming exposed in further lies about the non-existence of sectoral analyses of its consequences. You can bet your bottom dollar that the work on those sectoral analyses was done and that they exist in draft form somewhere in the deepest cellars in Whitehall They don’t officially exist because the drafts weren’t finalised. That is the oldest trick in the manual on how to deceive parliament – believe me.

David Davis’s role as a red-faced contortionist was amusing to behold. But all of the contortions remind me of Seamus Mallon’s line about “Sunningdale for slow learners”. The Tory party and their attack dog friends in the media are engaged in “Soft Brexit for slow learners”.

What can we do in the meantime? Persuading Sweden to re-open its embassy here might be a start at building new EU friendships and alliances.