The creation of an independent Irish state in 1922 has turned out to be a good thing for the great majority of Irish people. While you may read about Irexit (and a small minority believes in it), no group of any significance now believes or argues that Ireland should re-join the UK.

And while Irish nationalists won their demand for an independent Irish Free State in 1922, there was no chance that Britain’s then government, a coalition of unionists and Lloyd George liberals, was going to impose a settlement which drove northern unionists out of the UK against their will. Nor were the Irish negotiators in any position to secure such an outcome.

Indeed, it always seems strange that the anti-treaty side believed that the only acceptable and achievable outcome to their struggle for independence at the time was an Ireland entirely outside the commonwealth but incorporating the six counties.

Quite apart from the British army presence in Ireland in 1922, the UK government had deliberately armed more than 20,000 unionist police, including special constables – as is made clear by Michael Farrell in his book, Arming the Protestants: the formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary, 1920-7. This was at a time when the IRA had, perhaps, 4,000 weapons at its disposal. Northern Ireland had been established as a self-governing part of the UK in 1921, under the Government of Ireland Act enacted in December 1920, and was not to be abolished or dismantled by nationalist or republican coercion.

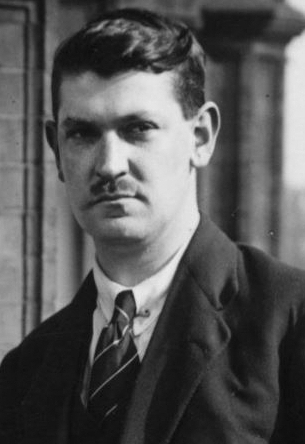

What did happen is that the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland ceased to be in 1922. The mother-country of the largest empire on earth no longer existed as a unitary state. That is what Michael Collins and his War of Independence achieved. Together with the IRB, he saw that accomplishment as the most that could be achieved at that time. An independent Ireland with the same status as Canada within the British Empire – in a process of rapid transformation following the end of the Great War – was, in their judgment, the best foundation for the ultimate creation of a wholly independent Irish republic, as happened in 1948 – freedom to achieve freedom.

One thing that fascinates me is airy dismissal of any likely outcome to the failure of the treaty negotiations. Whether or not Lloyd George’s Downing Street threat of immediate and terrible war was rhetorical bluff, very few Irish historical analysts have examined or described what might well have happened if the treaty talks failed.

By October 1922, the conservative and unionist majority in his coalition had effectively dumped Lloyd George whose position had become increasingly vulnerable in 1921 and ‘22. If the treaty had not been agreed by then, would the Tories, in government on their own, have delivered its substance? Or might they have been tempted to impose a much more unionist outcome, modelled on the Government of Ireland Act 1921 which preserved the UK with subordinate home rule parliaments, north and south? Could they have done so on the pretext of avoiding a Green-Orange civil war in Ireland?

One difficulty we face now in examining these issues is that Griffith and Collins had to sell the treaty in early 1922, while keeping confidential their own analysis of the political fragility of the Lloyd George coalition. Were they aware, for instance, of 1921 machinations by Churchill and Birkenhead to depose Lloyd George, as recorded in the diary of Frances Stevenson, the premier’s confidential secretary with whom he had an affair? Did they sense the potential of an early departure of Lloyd George and a resumption of Tory rule in London? Could they have picked up the very real possibilities and risks of failure of the treaty talks from side-talk interactions with the British side in late 1921? Could they credibly explain these confidential matters to the Dáil or to the Irish people, while Lloyd George was still clinging to office? The deaths of Collins and Griffith closed off any such possibility.

My point is this. Much current discourse of the treaty dispute and its outcome blithely assumes that an independent Irish State in the form of dominion status and the end of the old UK were, so to speak, “in the bag” politically.

Accordingly, further advances such as De Valera’s idea of external association were worth risking a breakdown within the Lloyd George coalition.

There is a very different scenario in which the ultimate independent Irish State was no foregone conclusion. That scenario might include failure of the talks, blaming the Irish for intransigence, the deposition of Lloyd George as prime minister, the earlier end of his coalition, a hawkish Tory administration playing the avoidance of Green-Orange disorder card, and the imposition of the Government of Ireland Act, 1921, backed by martial law.

From a start point in 1911, an independent Irish State by 1921 seemed improbable. Courage and statesmanship brought it about.

The same now applies to a united Ireland. Exactly what package would persuade a northern majority to vote Northern Ireland out of existence? Confederation or Sinn Féin’s unitary socialist republic?

Photo credit: By Agence de presse Meurisse – Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18536118